This was originally published on December 28, 2023, on Not Dark Yet, the Substack site of writer Peter Trachtenberg, who retired from our department last spring.

My friend and colleague Jeff Oaks died of cancer just before the Solstice. He was young and much loved, and his death leaves a void in the hearts of his friends and in the life of the University of Pittsburgh’s Writing program, where he taught for more than 30 years. Along with instructing generations of young poets, he mentored many colleagues, including some who were better paid and occupied higher niches in the academic ecosystem. One of the reasons I became active in Pitt’s then-emergent faculty union was because I saw how hard Jeff and other non-tenured (‘appointment stream’ is the University’s preferred term) colleagues worked, teaching more courses for less pay and without the security of tenure, scrabbling for time in which to write. If I hadn’t joined the union, I wouldn’t have been able to look those colleagues in the eye.

I don’t feel equipped to write a eulogy for Jeff. Other people knew him better and are more deeply hurt by the loss of him. Since many of them are writers, I know they’ll do justice to the beauty of Jeff’s person, his humor and kindness, his generosity, his unpretentious egalitarian spirit, his love for his husband and friends and students and dogs, and of course the English language, especially in the space of the poem, where the language attains its fullest and most vital expression.

I can’t say I feel equipped to write about him as a poet, either, since in all my years of writing I’ve produced only two or three poems I would dare show another person, so what do I know? Still, what I love about Jeff’s poems, which are collected in two books, Little What and The Things, is their seeming casualness, the way they arise out of moments of lost time, time that ordinarily goes unremarked, unnoticed. Some poets would make it their project to open those moments into vast tableaux. Jeff leaves them small, their modesty intact:

This darkness needs a praise song to survive it.

A song remembering what’s inside each egg.

The before and after. How much is spent

gratefully in darkness. Asleep, alone,at peace.

— from "Lines During the Solstice" (Georgia Review, 2018; The Things, 2022)

Although I never took one of Jeff’s classes and had already taught for some time when I came to the University, no one taught me more about teaching writing. In his syllabuses he met students where they were, then took them higher. Understanding that most undergraduates (and most grad students and, yes, many writing professors) want to write about themselves, he showed them how to do so with boldness and self-discipline. He showed students how to use notebooks not just as staging grounds for poetry but for every creative endeavor. He was a wonderful artist, and when you came upon him in the coffee shop that was his second office, he was as likely to be drawing as writing. He liked colored pencils. His characteristic pattern was a loose grid of rectangles of various sizes and colors that suggested the patches on a worn garment. Sometimes he pasted in scraps of paper with lines of poetry typed on them, the lines ghostly beneath a wash of pigment, the poetry of the half-hidden. Those pieces would have made beautiful stained-glass windows.

Among the many gifts he gave his students was his unselfconscious modeling of what it means to be a poet and artist in the world, using all its materials to create.

Against my will this is turning into the eulogy I said I wouldn’t write. Maybe my only way out is to speak more generally about what Jeff taught me or that I picked up by eavesdropping or reading his syllabuses or talking with students who’d taken his classes. So a numbered list, easy to write on a chalkboard:

1. Say yes. Instruction in any creative medium begins with permission. Nothing will happen unless you tell your students yes. Nothing will happen at your own desk or easel (do painters still use easels?), in your rehearsal space or studio or at your laptop unless you tell yourself yes. The creative act recreates the play of childhood and the games you made up for yourself then, sometimes for friends. When you played those games, nobody told you no unless your mom caught you climbing too high or preparing to duel another kid with the ski poles. Nobody could complain you were breaking the rules; the rules were yours, you had made them. Sadly, as you got older people began to shame you out of those games and the spirit of invention from which they came. Mostly they did this by saying no. The worst was when they said it in a tone of exasperated disgust, as if you ought to know better than to even try doing what had suddenly been forbidden you. Stupid, stupid you. In this way you grew up. Now as a grown-up teacher of writing, your first task is to say yes to your students and, with more difficulty, get them to say it to themselves. Yes to the feelings they never dared admit they felt. Yes to the image that no one ever saw before, not even in their mind’s eye. Yes to the ugly things as well as the expected beautiful ones.

Be sure to say this to yourself, too.

It can be hard to bring about this state of permission. Often you have to use trickery. “I love showing students my own tricks to trick my own mind and language out of its familiar habits, and I love challenging them with tricks I’ve picked up from my own teachers and from the many many writers I know and read.” This is from Jeff’s 2023–24 renewal letter, the last he would write before his death.

Under his influence, I too developed or acquired a repertoire of tricks. A case in point: After seeing how hard it is for many young writers to render action, even the simple action of someone running out of the house to catch a bus, I adapted an exercise1. in which students watch a two- or three-minute scene from a movie or TV show and then write a precise transcript—what the characters look like, what they do, what they say as they do it. The goal is to be as thorough as possible, so that a stranger reading the transcript would immediately recognize the scene if they came across it on YouTube.

The transcripts can be dauntingly long, and partly for this reason the assignment has a second part, which I usually ask for the following week. The students review the same scene and write a sort of summary, using elision and condensation to speed up the action and figurative language to convey its emotional tone. At the end of the sequence they should know how to recreate action with economy and emotional vividness. They will also know firsthand why economy is desirable, because transcribing those scenes at full length is unbelievably tedious. So is reading them. I’m pretty sure ChatGPT could write the transcripts, but it would probably do that so well that a teacher would immediately make them as fakes or forgeries or whatever it is we call work that is made by something inanimate: a plagiarism, which derives from the Latin plagiarius, "kidnapper." Something so tedious yet so grammatically and stylistically correct could only be produced by an entity that never gets bored.

2. Say no. Almost as important as saying yes is saying no. No to the worn conceit, the unthought-out line. No to the fantasy story where slain characters come back to life or reappear in another dimension because the writer suddenly decided they could. No to the assignment one hands in just because it says so in Canvas and maybe the professor won’t notice. No to the almost-as-good. Another word for this is rigor. Without rigor, the writing class conforms to the slanders of cost-cutting university presidents and state boards of regents. It’s merely a place for students to express themselves, express here being a synonym for squeezing, as is done to oranges and zits. It’s therapy. At many colleges, Writing is less a subject than an annex of Student Counseling services, and we know how much most colleges spend on that.

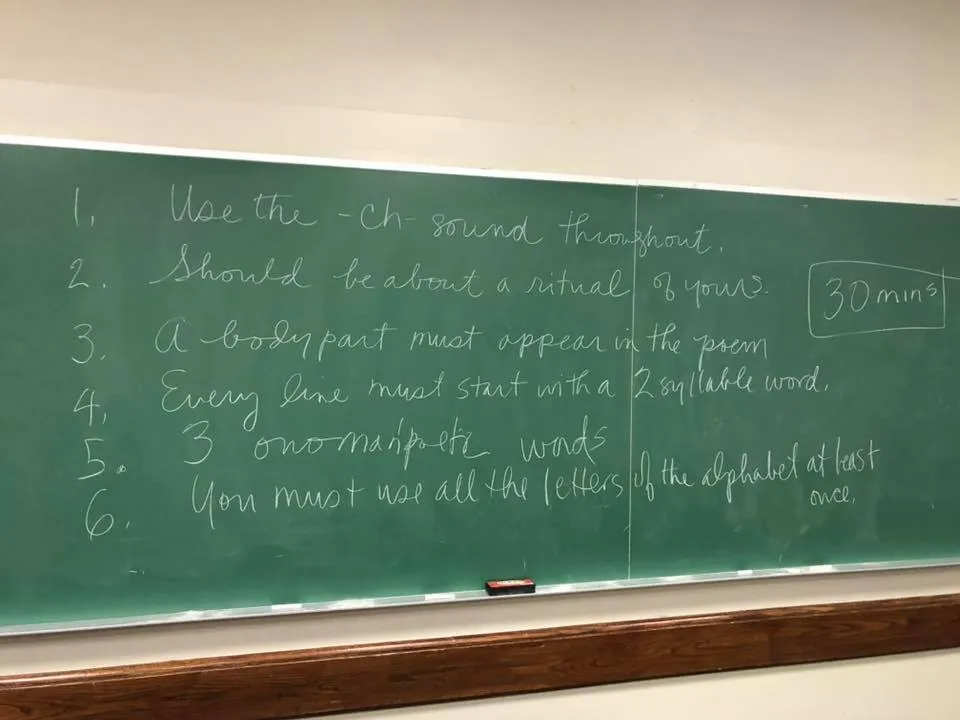

Rigor discourages all manner of bad habits but it also stimulates creation. If you don’t believe me, open a notebook and for the next 30 minutes follow the prompt Write Anything. Now show me what you wrote. Not much, huh? Now follow Jeff’s prompts for a “Garbage Poem.” I’ll bet you you write more. You’ll do this because the prompts carve out a discrete space in what was formerly infinite. Who can even conceive of infinity, much less begin to fill it? In the quantum of creative writing pedagogy, saying no is a way of saying yes.

How you say no matters. You must be rigorous—even ruthless—but you don’t have to be mean. And unless you truly believe that your authority as a teacher is above question, you should explain the reasoning behind your prohibitions, though you can be excused for throwing up your hands when the same student persists in the same regrettable habit. They may do this out of ordinary human laziness or because something inside them is so freaked out by criticism that at the first hint of it their entire being clamps shut and whatever you said or wrote on their manuscript bounces off and drops into the oubliette of traumatic memory. Maybe one day it will be recovered under hypnosis. A very, very few of those students are confident that their way of writing—skipping action, ladling on the adjectives, scorning to provide facts or details that might ground their assertions—is really the right way, the only way, and everyone else has been getting it wrong forever, yourself included. You send these writers on their way, taking care not to grade them punitively, though God knows they were a punishment to you, andyou are not surprised when five years later you learn that they’ve gotten a contract with FSG. The book comes out to excellent reviews.

In general, rigor is secondary to permission—not less important but secondary. As a teacher, I try to refrain from saying no until I see that the student has truly learned to say yes, since if the sequence is reversed the student will never write at all. I try to do the same in relation to my own work, which I undertake with almost as much trepidation as my first-years undertake theirs. When I started my last book, I wrote WRITE F***** UP on an index card and pinned it to the wall above my desk as a general license to write a mess of a first draft that I could clean up in revision. So permission followed by rigor, yes, then no. It’s like playing the accordion, the alternation of dilation and contraction. William Blake, the rebel angel of English (and maybe all) poetry put it this way: Damn braces, bless relaxes.

On consideration, I think "no" may be a mistake. Jeff would have said "Yes but."

3. Pay attention. Both permission and rigor require attention: that of the teacher to the student, that of the student to the teacher, and that of both teacher and student to the text. Young children treat their teachers as surrogates for their parents, and the attention they pay them is often deeply personal, informed by the same trust or deformed by the same fear and resentment they feel for the latter. But in college and graduate study, the teacher is an intermediary for the text, the text being the student’s writing as well as the poems, essays, or stories assigned in the syllabus. A transformative teacher pays such lucid, concentrated attention to the student’s writing that it is revealed to its creator for the first time. For the first time they see the beauty of what they are creating as well as the defects that occlude it like fingerprints on a windowpane. In the same way, the teacher shows them how something written by a stranger—maybe in another country and hundreds of years in the past (Sophocles! The Lady Murasaki! Rumi!) may show them a way of addressing those defects.

This can happen even if the student dislikes the teacher (though probably not if they fear them) and even if the teacher dislikes the student, as long as they still feel responsible to them and their common enterprise. But the ideal condition for the concentrated exercise of attention is love. “Love” is the word that comes up most often in Jeff’s teaching statement. It’s one indication of what an inspirational teacher he was. “What is still true,” he wrote, “is that I have no idea what out of all their desires my students want to work on/with, that at least half of my teaching work is to listen well and improvise on the spot. I love that I get to show them ways to keep those contacts alive, how not to disappear into mere survival, and how large a reservoir of literature there is to help them stay conscious and full of joy.”

What better thing can a teacher give their students than the means for staying conscious and full of joy?

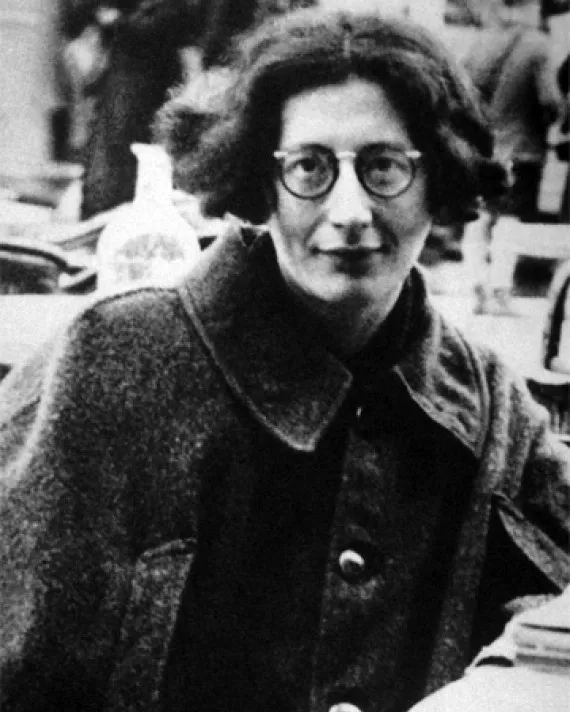

Simone Weil, the greatest and wildest of the French thinkers, believed attention was synonymous with love.

“The poet produces the beautiful by fixing his attention on something real. It is the same with the act of love. . . . The authentic and pure values—truth, beauty and goodness—in the activity of a human being are the result of one and the same act, a certain application of the full attention to the object.

"Teaching should have no aim but to prepare, by training the attention, for the possibility of such an act.”

1. I think I got this exercise from either Amy Whipple or Nikki Carroll.

—Peter Trachtenberg

Peter Trachtenberg retired from the Department of English last year. He is the author of 7 Tattoos, The Book of Calamities, Another Insane Devotion, and the forthcoming The Last Artists in New York (forthcoming from Black Sparrow Press) as well of essays and short fiction published in The New Yorker, Harper's, and the Virginia Quarterly Review. He's the recipient of Whiting and Guggenheim fellowships, and of the Nelson Algren Award for Short Fiction.