Pitt MFA alumnus Cameron Barnett

On a sunny April afternoon in the Cathedral of Learning, John Ferri, who recently graduated with a Public and Professional Writing certificate, sat down with accomplished University of Pittsburgh Poetry MFA alumnus Cameron Barnett, finalist for the 49th NAACP Image Awards and winner of the 2017 Autumn House Press Rising Writer Book Contest.

Over the course of their conversation, Barnett dove into the inspiration behind his first full book of poems, The Drowning Boy’s Guide to Water (Autumn House Press, 2017). He also paid tribute to mentors at Pitt and Duquesne, where he completed his BA, and showed us a possible future for great Pittsburgh writers—his precocious students at the Pitt-affiliated Falk Laboratory School. In conclusion, he tied together three central threads of his career—teaching, blogging, and poetry—with the fundamental power of telling your own story.

Falk Laboratory School: The Student Becomes the Teacher

John Ferri: Let’s start with your teaching career. You’ve been at the Falk Laboratory School for a few years now, and you’re an alumnus as well. Is that correct?

Cameron Barnett: Correct.

JF: So, what’s it like to teach at a laboratory school?

CB: It’s very freeing, in a sense. And it’s also interesting as an alumnus of the school. That is my foundational experience with what schooling is supposed to be. I think another person might say, “That is very different to start off with,” but for me, it’s very familiar. So, the idea of a laboratory school is that research can be done there and that even with the teaching methods, the ideas behind them should constantly be refreshed and updated, and not just resting on the laurels of something that worked once, or good research from a while ago. It’s really freeing and really thrilling, in a way, to be able to create your own curriculum. To get to tweak it how you want to. It isn’t like you have complete unlimited authority, obviously, but definitely more than you might in the public space. There’s a pressure there, too, to keep your work fresh. To make sure that you’re engaging the students year after year, not just to say, “Oh, my seventh graders last year had a blast with this unit, so it’s guaranteed to work with the next class.” You kind of have to adapt to each set of kids, because they’re obviously unique.

JF: Right. So, do you find that the school is somewhat avant-garde or experimental with its approaches, and focuses a lot of new pedagogical techniques?

CB: Sure, yeah! We’re always, as a faculty, discussing established research and also new research. We’re always asking ourselves those critical questions about how our pedagogy is reaching kids, reviewing or thinking about the psychological and developmental needs of kids. While also trying to bring in things that are different. The whole idea with our school, not just as a laboratory school but as a progressive school, is to let the children’s interests be at the front of whatever it is that we’re developing for them. For instance, with poetry, I don’t go in there and say, “All right, you need to know what every type of stanza is called, and every poetic form, and the history of the poet who created it.” My approach with that is to think about, you know, “What questions do you have about poetry? Are you interested in it? Why or why not?”—and then let that lead to their own exploration of the form, their own questions, with some guidance and some expectations that I set up myself, but I think, especially with something like poetry, which can be for most people kind of frustrating when you’re learning about it when you’re younger, I really try to pivot that experience and focus on something more positive for the students.

JF: And that’s interesting, because a lot of traditional pedagogy relied on broad memorization and figuring out the whole structure of a form, and then there would be very set things for students to explore. So it’s interesting that your students leave this approach. How do you structure your classes to help the students be productive and explore things in their own ways?

CB: It’s almost like an à la carte menu. I have them write a lot of poems. One-off poems. And then the idea is that they are creating these to lead up to their own poetry chapter-book. If I said at the beginning of the year, “Oh, you’re going to write a book of poems,” then they would be like, “What are you talking about, Mr. B?” But [I find it more useful] to say, “OK, what if we try this? What if we make a poem that does that?”, and then see what does and does not gravitate toward them. Then, I like to really push kids with some boundaries, too. Not to just say, “OK, here’s this form,” but maybe throw a critical question at them—write a poem about loss and explore that concept. It could be something as small as “I lost my favorite toy playing in the yard” or “I lost someone who was really a good friend to me” or “I lost a grandparent.” Then, if I need to, I’ll throw out some lesson plans along the way. That’s really thrilling to me, as a poet, to say, “This isn’t really gravitating with them, but that is.” Each time, the culmination of the unit turns out differently.

JF: That’s interesting. Do you find that taking a creative approach, as someone who is a creative person, is really beneficial for this form of education—as opposed to taking a more traditional and very structured approach?

CB: I think there’s value to a multitude of approaches in any discipline, but I think poetry is such a cerebral thing already that if you teach it in the way that it’s discussed in the adult world, there’s nothing clutching it to the interest of a child. But if you say to a child that poetry is a place where you get to create the rules and you get to break the rules that you’ve been told are sacrosanct … and you get to invent worlds and spaces and sounds and ideas and everything is in the sandbox of your imagination, so build me a castle … that is way more exciting to kids, because then they get to define for you what poetry is. What they produce is authentically them. That’s what they're proud of. That feeling of pride in an artform could be applied to woodworking or music or many other disciplines, but that’s absolutely how I love to approach poetry.

JF: Do you prefer to have the students focus on something that’s personal to them?

CB: I have a personal philosophy, and this too falls under the “laboratory” thing. I try to question and read work as I see fit for different groups of kids. I have the idea that there’s nothing more powerful than telling your own story. You can copy another poet. You can talk about themes that have been written. But, if you only look at it that way, it’s only going to be so much. But I always tell kids, my poems are stories. And they’re my stories. Only I could tell them the way that I tell them. There’s something very powerful about that. It’s something that really pushes kids to their comfort-zone limits sometimes. They say, “I’m only twelve or thirteen. Nothing interesting has happened to me yet,” or “I don’t want people to read this,” or “I don’t know what to say about myself.” Those are the immediate roadblocks that kids hit, but I find that if you sit with that a bit and know how to talk with them through that, they will usually surprise you and come to find something in the arena of what you’re looking for.

JF: Good to hear. What’s it like to teach and mentor kids in middle school, when they’re at such a critical stage in their development and their education?

CB: It’s a lot. It’s a big responsibility. And I think that’s what attracts me to it. There’s a challenge of trying to reach every child. You’re not going to be some sort of savior for them. You can only do so much. But just being there is the work. It’s a time where they’re establishing identity and independence, pushing away from traditional things, like parents, and maybe some friend groups. Everything is shifting. At the same time, they really need a role model, somebody older to look up to. There’s that whole other side of teaching that you don’t necessarily see on the homework assignments. I can stand in front of a group of kids and say, “I’m not just teaching you poetry out of a textbook. It’s something that I love to do.” And they think, “Oh, well, maybe if Mr. Barnett loves this, then perhaps I’ll love this, too, and other people will.” Kids are awash in a lot of different experiences. Meet them where they are. I find that really fulfilling.

JF: Does teaching inspire and influence your poetry at all?

CB: I think it does. When I put ideas out to kids that I’ve talked about in graduate workshops or in my own experience doing readings—to get a child’s feedback on it can be surprising or humbling. Even before I came down here [to the Cathedral for the interview], I was having a writing club that I hold after school. I had a debate with a really stubborn sixth grader who really thought that his haiku was poetry. And I said, “I know what you mean, but I don’t think that there’s enough craft happening in what you wanted to do here.” And the kid just wanted to argue the point, which is a very adolescent thing to do. So, moments like that sort of make me think, “What are the things that I like to do in a poem?” I like to share my own poems with kids in the units that I do, and they’re really quick to point out patterns or habits or obsessions that they notice in my poetry. So then, I start to get a little self-conscious and say, “Well let me switch it up a little bit!” Even seeing the way that a kid grapples with a prompt that I give them—that might make me question the wording of a prompt. What is it that I find in a prompt that I gravitate toward? How can I meet them halfway? So, just a lot of internal questions really come up for me, in that regard.

JF: Do you teach anybody in that realm who reminds you of yourself at that age?

CB: I don’t know if there is a certain child I could think of who’s like me, but there are many of them who have shades and streaks of what I was like in them. I ask them, “Do you think I loved poetry when I was your age?” And they say, “Yeah! Obviously!” I tell them, “No, I couldn’t stand it.” I was being taught the dry canon of dead poets. I could see that there was a lot of work going on in what they were writing, but that didn’t inspire me at all. Kids point that out to me, too. Their interest or love of poetry isn’t inspired by me handing them a poem someone wrote, or trying to talk through the poetic elements. They’re much more inspired by the idea that, “Oh, I get to create something of my own? I can sit down and do this now? I can create my own rules, get to create a stanza or a form?” That is so much of what inspired me to write in any genre. This is a space where I can create my own rules. That’s what gets reflected back to me from them.

JF: I imagine that being a practitioner, instead of somebody who just understands the theory of poetry, inspires a lot of kids. Do they see that there’s a track for them, then?

CB: Yeah. So many of the kids in my class see themselves as artists. There’s a strong artistic potency in the school. They look at me, and they like to ask a lot of questions: “Do you read at a lot of places? Do you get nervous? Do you make a lot of money?” So many kid questions! You know, sometimes, kids with too many questions can be frustrating, but you always remind yourself that this is them showing their genuine interest, and if I make this sound as interesting to them as it is to me, genuinely, that is an inspiration that could carry over for them.

JF: Do you teach any students who are struggling with personal issues that are reflected in their poetry and find a great outlet in that?

CB: My kids have no qualms about writing about some pretty personal experiences, whether it’s drama in their friend groups, or the health and wellness of older relatives. Cousins. Extended family. And they write about those things very tenderly. Sort of by accident, not by me teaching them that this is a simile or that is a certain form—they’ll just write about really profound experiences in their lives. It’s always special to see that they chose to do that. I never tell kids to take something really difficult and write about it to impress me.

JF: What’s it like to be an alumnus of the Falk School?

CB: I loved going to school there. It’s a school that just feels like a place where people care about you, they’re invested in you, they know you. They’re always trying to make your educational experience not only rich and rigorous, but interesting to you. So even before I thought that I would be back there, I had a nostalgia for Falk. Coming back as a faculty member, I was really nervous, thinking, “Am I able to do this?” There are also teachers who are still there that I had when I was back there. It’s a cool dynamic, but sometimes strange being on a first-name basis with people you called “Miss” and “Mister”! I had no real set opinion on working with kids when I graduated from the MFA program at Pitt, but from the first day that I got to Falk, I saw that this is awesome! The kids want to learn in a way that’s much more obvious than older students, and that’s infectious.

Blogging: Perspectives on Poetry, Pittsburgh, and Antwon Rose

JF: So, you’re also a blogger, with a website, cameronbarnett.net, and you write in your blog about Pittsburgh, about your poetry, and about poetry in general. I saw that you wrote something about how Pittsburgh is called one of the most livable cities in America. And you wrote about how it’s interesting that it’s “the most livable city” for some, and not for others. You wrote about the difficult and controversial situation with Antwon Rose’s death, the underlying dynamics around issues related to that, and segregation problems in Pittsburgh. Can you talk a bit about that?

CB: Sure. There’s a big sports culture in Pittsburgh, and a culture of success, and a sense of community, and family, and connectedness, and unity. All the teams wear variations of the city’s colors. Everything speaks to this oneness of the city of Pittsburgh. It’s a really easy thing to get caught up in because it feels great. But when you look critically at the history—the red-lining that was done in the New Deal era, opportunities that certain segments of the city have that others don’t ... even comments that you see online whenever some piece of news happens in the city show how polarized it can be. You realize that living in Pittsburgh is not one-dimensional. Depending on where you come from, you have a certain narrative of the city. Black Pittsburgh is often-times in this space of conflict between staying and investing in this city that has a lot of very rich history in particular to African-American culture, or leaving because in a lot of ways it’s a hostile place to work toward your identity, toward your aspirations, and your opportunities and access to education and health care. A lot of times the narrative that comes out in the media—our lore that we create about ourselves—can sometimes whitewash the image that people have about Pittsburgh. It’s a fabulous city in a lot of ways, but it is not equal for everyone. With what happened in the Antwon Rose case, even though that happened in East Pittsburgh, it’s something close to home. You can have something like that happen, and have polarized reactions. That speaks to the fact that we’re not on the same page. And we need to have a higher standard of being connected.

JF: What do you see about your contributions to arts and literature that go with the Pittsburgh tradition of great arts and literature, with names like Ahmad Jamal and Erroll Garner?

CB: I certainly don’t put myself there in that tradition. I would hope that somebody else would put me there in the future! And I wrote in the book about seeking an understanding about where one sits in a sort of racial pool. I have poems in my book The Drowning Boy’s Guide to Water that explicitly deal with how my grandfather on my mother’s side was a civil rights leader in this city—a well-known and well-respected clergyman who worked in the Hill District and was involved in a lot of desegregation efforts. He literally rubbed elbows with civil rights leaders we study about in textbooks, all the way up through Martin Luther King Jr. I’m two generations removed from that. What is it that I do in my own life that ties in with that legacy, and do I owe anything to that legacy? If so, what is an appropriate or sufficient way to contribute to that legacy? One other thing I want to say relating to the mix of ethnic persuasions in Pittsburgh is there’s that moniker in Pittsburgh that it’s a city of bridges. I love that. And it’s so true. There’s so many kinds of people here. And the roots run really deep. But I think it’s also a city of rivers, which I think we realize in some ways. But at a metaphorical level, we tend to think about the bridges because it’s easier. We don’t think about the rivers metaphorically as barriers. I have a friend who grew up on the South Side and talks about how her parents and grandparents remember a time when crossing a bridge from one neighborhood to another could get you into a fight. There’s a lot of barriers that have been here and often do tie into the geography. I think, in 2019, we’re doing a lot better in some ways at bridging things, but the rivers do still exist.

Constructing a Poet: Growth and Practice at Allderdice, Duquesne, and Pitt

JF: In The Drowning Boy’s Guide to Water, in your poem “Solemn Pittsburgh Aubade”, you write about black and gold bones, Pittsburgh sports, Mount Washington—but also the very different experiences people have in various parts of Pittsburgh. Is there anything you want to say about that, what inspired the poem, and what you hope people take away from reading it?

CB: That’s a poem that I remember writing one morning at a friend’s apartment, doing a summer workshop together. And I took the first two lines in this from the end of a poem by a fellow Pittsburgh poet, Scott Silsbe, and built on the idea of houses being on fire every night. Which is a very Pittsburgh thing, you’ll realize. On the news every night. It’s another way I was trying to locate a sense of identity. I built on the neighborhood experiences in Pittsburgh. There are people who were born here and lived in Squirrel Hill all their life. Or they lived in Oakland all their life. To them, that’s home. For me, I lived in Swisshelm Park and went here to Falk, then I went to Allderdice [High School, a Pittsburgh public school in Squirrel Hill]. I lived in Mount Washington. I was on “the Bluff” at Duquesne University. I had apartments all over the city—Squirrel Hill, Greenfield, Garfield—while I was in graduate school. In a way, many neighborhoods feel like home to me here. I’m trying to express the pain and pleasure and love that I’ve experienced while being in different locations. It’s pouring out of the poem. My favorite couple of lines in this poem are toward the middle, where I say, “One time I loved somebody. One time, I crossed this street when I was in love.” There’s a vagueness, but also a sort of specificity, that you remember where you were when you experienced a certain strong emotion.

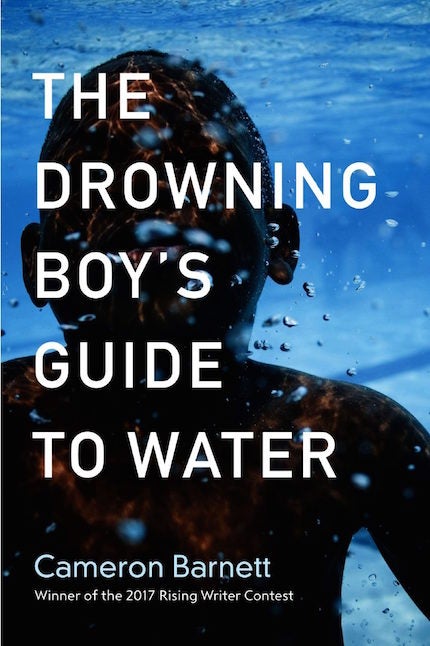

Cover: The Drowning Boy's Guide to Water

JF: You studied for your bachelor’s in English at Duquesne. What was that like, and how did it shape your writing and poetry in particular?

CB: Sure. I have to go back to high school to really answer that question. I never really saw myself going into a field like business, law, or medicine. I had a feeling that I’d just keep growing up, and then I would figure it out. In high school, I started writing this long novel—really a big half-fictional, half-true journal of events going on in my life. So I established that I loved to write. I was doing that all the time when I probably should have been doing homework a little more! It was a natural choice to study English because I’d probably get to write a lot. My experience at Duquesne was really good. I had great professors who helped me improve all aspects of my creative and formal writing. But I have to give a particular shout-out to Dr. Linda Kinnahan. I fell into her class almost by accident, meaning to sign up for another class with a group of friends. I showed up to her poetry workshop my sophomore year, and she had me doing all kinds of creative activities—cutting up words, pasting things together, remixing different poetic genres. All kinds of stuff, where I was like, “Wait, we get to do this with writing?” And it’s creative. And I get to tell stories, but also to sharpen and play around with language. I was lucky enough to take two more successive workshops from her, and that consistent year-and-a-half of working on poetry really made me feel like writing isn’t just my hobby. This is something that I love to do, and it’s built into how I think and breathe and view the world. I’m wasting my time if I’m not spending my time doing that.

JF: So you found your passion?

CB: Yeah! Duquesne absolutely helped me find that.

JF: So, then, you went on to get a master’s at Pitt in Writing?

CB: Yes, a master’s in writing, doing the track in poetry. I had no idea that MFA programs in poetry existed until Dr. Kinnahan mentioned them to me. And when I found out that there was a program here at Pitt, loving being in the city, I was determined to get into it. Very fortunately, I was able to. I worked with great people here—Terrance Hayes, Lynn Emanuel, Dawn Lundy Martin, and several others—who all challenged me in different ways. I’ll never forget that I wrote a poem that had some very trite imagery of a butterfly, and in my first workshop with Terrance Hayes, he said, “We need to work on that. You can do better than that image.” It really kicked me into a higher gear with my writing. I don’t think The Drowning Boy’s Guide to Water would be possible at all if it weren’t for the teaching that I got here.

JF: Would you say that Terrance Hayes [professor of Poetry] was one of your mentors here at Pitt?

CB: Absolutely. He was someone who I would meet with often in office hours, not just for class purposes, but for my own personal guidance. How do I make my writing sharp and interesting? How do I write about blackness when I’m not sure how to even comfortably locate myself in black culture sometimes? He was instrumental, along with Yona Harvey [assistant professor, Writing], in guiding me through that cultural identification experience, to make me feel like I had some authority to write about and be who I am. It’s something that they profoundly shaped and helped me with. I can’t credit them enough for what they did.

JF: Coming to the University of Pittsburgh was also a launchpad for some of the poetry readings that you have done. You’ve been a poetry editor for the Hot Metal Bridge, for instance. Would you like to talk about that experience?

CB: Sure. Hot Metal Bridge is the literary magazine that is primarily led by the graduate students at the University of Pittsburgh in the Writing MFA. It publishes fiction, nonfiction, poetry, and sometimes reviews. It was my first actual experience on the editorial side of a journal. I submitted a lot of work to Duquesne’s journal, Lexicon, but getting to be on the other side, looking at submissions and seeing how we want to put these poems together, or whether we have a theme that we want to work with—these questions of craft in which a poem is one unit within a larger creation—was unique to me.

JF: Now, going back to your book for a bit, are there any comments you would like to make about The Drowning Boy’s Guide to Water?

CB: I always say that the title is a nod to the fact that the narrating voice is quasi-unreliable. The worst person for advice about drowning is someone who’s drowning, because they’ve succumbed to the element. But at the same time, the best person to speak to about drowning is the person who’s drowned, because they’ve had the experience, viscerally. Carrying that metaphor about drowning forward into blackness and cultural identity in general is where I position myself, at times, and at [other] times, a more nameless narrator for some poems—someone who’s trying to figure themselves out. So, the title is borrowed from a friend of mine who wrote a story called “The Drowning Girl’s Guide to Water”, which I just love, and we were talking things through. We agreed that if we remixed that title a little bit, it would work for a title of a book, so I have to give a shout-out to my friend and roommate Nina Sabak, who gave me that idea. It’s something that people love to talk about. It’s a great title. And I owe it to her.

JF: This book is also a way for you to continue to grapple with blackness in the United States, and your own personal experience with that culture and that ethnicity. Is there anything that you remember from your experiences as a child or as an adult that stands out, or anything that you would like people to know about black culture in the United States?

CB: I say this a lot, that no ethnicity or people—especially African-Americans—is a monolith. There’s a poem in [my book], based on a real experience I had, going to school at Falk really early in the morning, probably in third or fourth grade. I was having a tantrum, yelling to my mom that I just didn’t want to be black anymore. I don’t even remember what caused that feeling. I wanted to shed that skin because I didn’t understand the things that people were saying to me about it. I wanted to be accepted. I wanted to be normal. To fit in. And to me, that meant being white. And then as you grow up, you realize how wrong that thinking is. You aren’t only one thing or another. You can be in-between. Having an experience like mine, being black but also having more privileges than most when I was growing up—more comfort, more opportunities in life, and not facing the same set of hardships as the average African-American—brings to my attention the question, “How black am I?” My skin certainly is. I can’t change that. But my experiences—how much do they line up with the overwhelming narrative in this country? And does that mean that I’m black, or am I white? Or can I find a place in-between? That’s what The Drowning Boy’s Guide to Water is trying to explore and crack open. It doesn’t have to be this “either/or” question. Because there’s a host of experiences in-between. And those experiences are just as important as any other experiences.

JF: Very interesting, and well put. Does this relate to your family’s history and role in the civil rights movement?

CB: Sure. I think that when your grandfather is a civil rights leader—local and sometimes national—you grow up and realize what the weight of that is. You have the impression, “Whoah! That is something I need to live up to!” I was raised a couple shades away from his experience, because of the fighting for opportunities that he did for us and for people like us. To be generationally and culturally removed from that experience is a shock, but one of the things that is unfortunate in one sense and fortunate in the other is that there is still work to be done to this day. The civil rights movement wasn’t a one-time thing in the ‘50s and ‘60s. It’s an ongoing experience that has been broadened across so many other identity categories today, but even the existence of groups like Black Lives Matter, trying to continue to update and change the narrative of lived experiences in America is something that is a modern civil rights opportunity. I was once asked by someone if I consider myself an activist, and I feel like that can be such a loaded term in some ways. I mulled it over, and I think that my activism really is my teaching. Through teaching the craft of poetry to kids—and all writing, not just poetry—there’s the idea that, by owning your own story and honing your craft and working on all kinds of writing, you can create a greater empathy for yourself and therefore for other people. Their experiences. The burdens they bear and the joys that they have. And my hope is that, teaching that to kids as young as middle-schoolers who are searching for identity, something about what I have to say will solidify in them as they grow up. That’s how I define my modern-day activism, if you will.

JF: You use a particular term here in your book, a term related to modern America that has become much less trendy now in the current administration, but was popular several years ago. Some intellectuals felt at one time that America was moving past racial discrimination, and moving towards what was called a post-racial society. One of your poems is very critical of that term. Is there anything in particular that comes to mind when you think of “post-racial society” and a “post-racial America”?

CB: For me, it goes back to what we were talking about with Pittsburgh, you know? Seeing the bridges but maybe missing the river. Seeing the fact that there’s a lot that can be shared and connected, but often to the detriment of seeing the existing barriers that are impenetrable for people. For me, the term “post-racial” has always been a joke, in a way. America—before it was even codified as a nation—had such deep racial tensions in it, so this idea of an America that exists without race is fantastical to me. It’s not something that I think we will ever get past. It’s something we’ll need to come to terms with. So, the poem is written as a sort of ten-question quiz that you might give out in school, but also with a ton of satire and metaphor—and vagueness, in a way—and is meant to point out how impossible and ridiculous it is to get at that question. If you can’t answer the quiz, is the question invalid? Is the terminology even valid? So that was what I was trying to express in that particular piece.

JF: That poem was called “Post-Racial America: A Pop Quiz”, and it’s towards the conclusion of The Drowning Boy’s Guide to Water. Does this reflect at all the sort of quizzes that your middle-schoolers get, if not in terms of the actual questions, then maybe the format?

CB: No, not at all! I actually have a really strong policy against giving pop quizzes! I don’t like to surprise students. This was really a poem that I wrote in one fell swoop in an afternoon—probably after a news clip about something that was happening between 2013 and 2016. It seemed like so much happened. And noticing not only the events themselves, but the conversation in the media and the conversation on social media, and the fact that so much wasn’t changing over large periods of time—months and years. What is it we’re all talking about? Let me quiz us. I’ll throw this out as a test you have to pass.

JF: So, could you talk a little about the craft of writing as well? You mentioned that news clips, personal experiences from years ago, and sometimes, things going on every day can inspire poetry. Is there a general way that you approach your poetry?

CB: I have two ways of answering this. My own approach to creating any individual poem often starts with gathering a lot of ideas that I’ve thought of, words that I think are interesting to use or have good sound qualities, bits of conversation, things from the media, or even just thoughts that I’ve turned over in my head for hours until I can distill them down to a certain phrase. I’ll keep a long series of notes in my phone. What I’ll often do is I’ll pick, mostly at random, a few that either could go together, or even ones that don’t have any obvious connections. And I always use the analogy of an artist with their palette and easel, dabbing bits of paint in different places. Over the course of the process and a few hours, a painting begins to emerge. I try to create those connections between those things. That is my crafting approach. But, another way of answering this is, to borrow from my mentor Terrance Hayes, that a poem should be about as many things as possible. I’m paraphrasing that. That, to me, was really intimidating but also a really cool idea—like a challenge! How could I make the lines of my poem mean many different things to as many different people as possible? So, usually, the spirit that I try to imbue a poem with is one where the metaphors, the imagery, the simile, the cadence, and all the fundamental elements that we talk about with poetry crash and collide together in a way where everyone knows what’s happening. But ideally, everyone also has their own unique experience and reaction to it. I want someone who’s nine years old and someone who’s ninety years old to both find something valuable in my work, perhaps in completely different ways. To me, that’s good poetry.

JF: As a final thought, what are some connections that you find, even if they weren’t originally intentional, between these three main aspects of your career—your teaching, blogging, and poetry?

CB: I always tell people that maybe I’ll write a book about this one day! And maybe I should stop saying that, because someday they’ll expect that I will. I have this thought that, fundamentally, all communication is story. When you think about early humans in their tribes, the thing that every single one of us did all over the planet was tell stories, whether they were real or imagined. That’s always been what binds us. And that’s the big cerebral picture of things, but when you break that down to writing a letter to someone, writing a persuasive essay, writing a poem, writing a diary entry, writing a blog post, or a Post-it note to let someone know something, it’s all communicating a story. There’s some narrative behind it, whether that narrative is on the surface of the writing or not. For me, when I think about my poetry, I have a narrative background, and I try to write stories and then condense them into smaller things, until finally, I’m like, “Oh, I’m actually writing poetry!” When I think of my blogging, I approach it as trying to craft a story that I can drag a reader in to to see a perspective that I have. And when I think of my teaching, it’s about trying to impress upon these kids the value of stories, saying, “You might be 12 or 13 years old, and just coming into who you are, but you already are preloaded with your own stories. Those are powerful and unique to you, and they’re fundamental to who you are. So use them.”

Listen: Cameron Barnett reads his poem, "Between Skin."

John Ferri graduated this spring with a certificate in Public and Professional Writing. As a Class of 2019 Pitt Italian grad, passionate musician, and global citizen, he use languages, arts education, and arts organization management as tools to promote mutual understanding between groups of people.