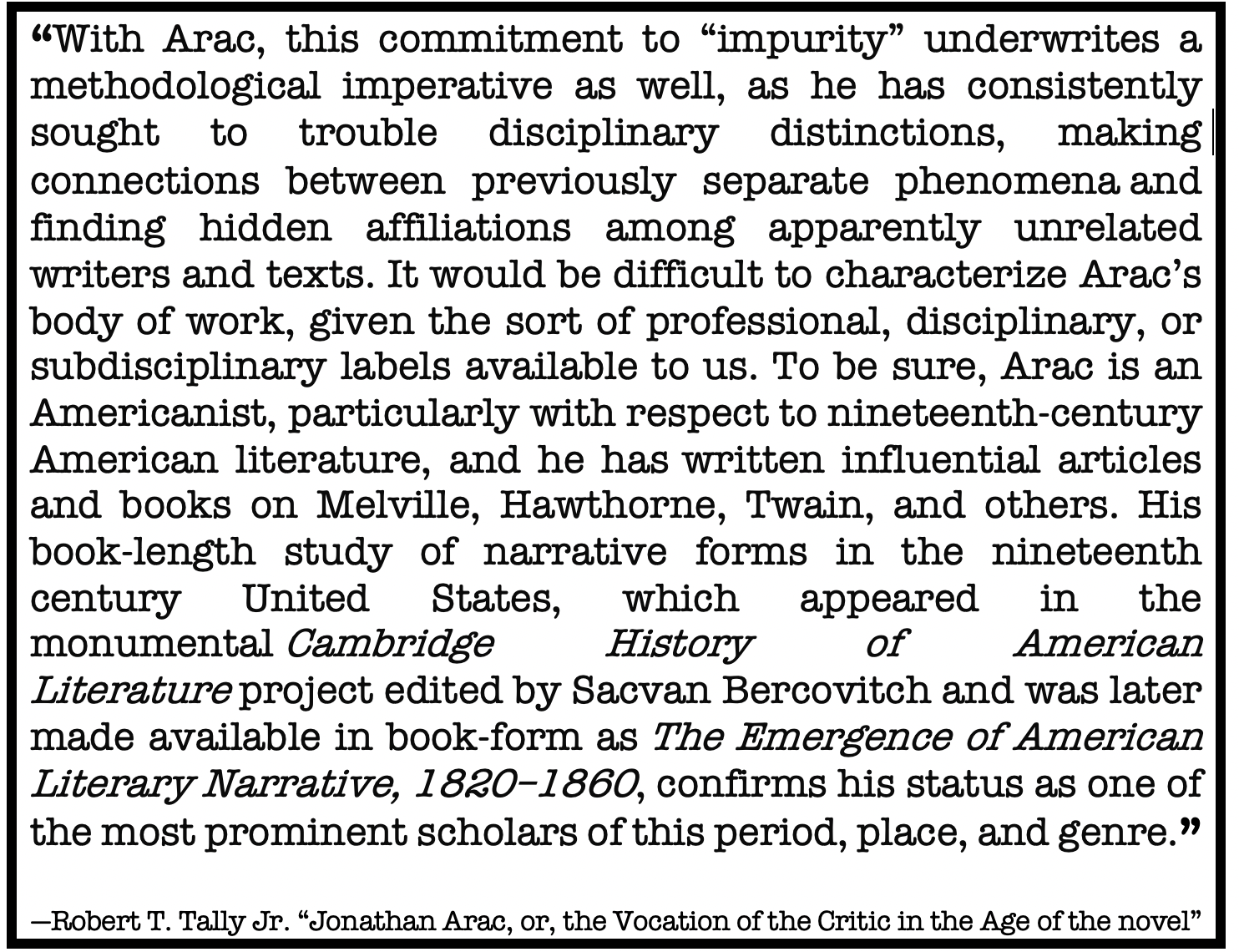

When I heard that Jonathan Arac was retiring, my first reaction was to feel sad for all the students who would not be able to take courses and work with him in the future. Not that he doesn’t deserve the break, of course, but Jonathan has always been such a marvelous teacher and mentor, in the classroom, in office hours, in casual conversation, and certainly through his scholarship and criticism. Anyone who has studied under his tutelage knows the incalculable value of the experience. I published an article a few years ago titled “An American Bakhtin: Jonathan Arac, or, the Vocation of the Critic in the Age of the Novel,” in which I focused my attention almost entirely on Jonathan’s writings, but I ended by noting that Jonathan is best understood as a teacher. His contribution to literary and cultural studies in the United States over the past 40-plus years is enormous, but his legacy may be more intensely registered in the lasting impressions he had made upon his students.

I can honestly say that Jonathan taught me how to read. He’s not the only one, of course, but he did as much if not more than anyone else to teach me the ins and outs of proper literary criticism. Having been a philosophy major who came to grad school primarily interested in critical theory, I had not really studied literature, literary criticism, and literary history very thoroughly. I knew of Jonathan as a Foucauldian critic, but I was more familiar with his work as an editor of collections on theory and criticism—notably, The Yale Critics: Deconstruction in America (Minnesota UP, with Wlad Godzich and Wallace Martin, 1983), Postmodernism and Politics (Minnesota UP, 1986), After Foucault: Humanistic Knowledge, Postmodern Challenges (Cambridge, 1988)—than with his own literary analyses.

Given my stubborn and naïve theory-headedness when I first arrived in Pittsburgh, I was not really able to appreciate most of Jonathan’s scholarship, which in my ignorance seemed all too “literary.” For example, I recall being told that one of the best examples of how Foucault’s theories of power could inform literary criticism could be found Jonathan’s first book, Commissioned Spirits: The Shaping of Social Movement in Dickens, Carlyle, Melville, and Hawthorne (Columbia UP, 1979), but when I read it, I saw only a couple of direct references to Foucault and tons of stuff on Romanticism and so forth. I didn’t “get it.” Some years later, of course, and in part because of my education at Pitt, I came to see just how revolutionary and perspicacious that study of the literary technique of “overview” in the nineteenth-century narrative truly was. In my own work, the idea of “literary cartography” owes a huge debt to Jonathan’s careful and nuanced readings in that book. Commissioned Spirits is still a major work, and if you haven’t read it yet, I strongly recommend checking it out.

When I was a student at Pitt, I worked most closely with Paul Bové, who became my advisor, and to this day I consider Paul my mentor. I think it is impossible to calculate his influence on me, and no number of citations to his writings or references to his classes could give an adequate estimation of his effect on my own writing and teaching. But Jonathan was always incredibly generous with his time and his advice, and my own work might justly be considered “Aracian,” given how much it owes to and follows from Jonathan’s wide-ranging and elegantly argued criticism of nineteenth-century American literature. Considering that, as a project and dissertation committee member rather than chair, Jonathan probably did not receive much in the way of institutional credit for these efforts on my behalf, I am all the more grateful for his generosity and support.

Let me offer the example of a specific course: Around 1993 or so, I took a class with Jonathan called Interrogating Canonicity, which focused on both American literature and the institution of American literature. The so-called “canon wars” were still raging at the time, so this course was timely, but it was rooted in the need to understand the conditions for the possibility of “wars” about literary “canons” to begin with. The textbooks for the course included both volumes of both the Norton Anthology and the newly released Heath Anthology of American Literature, the latter self-consciously edited and curated to serve as a canon-reforming, multicultural, and diverse response to the former’s presumably canon-centered selections. Thus, as students, we read a great deal of “American literature”—that is, the primary texts included in the anthologies—but we also examined the writings in the context of the structural formation and reformation of a national literature, as well as of the ways that national literatures are deployed and disseminated in society.

We were thus able to maintain or try to balance something like four distinct perspectives at once: (1) reading the text itself for itself, (2) examining its own historical contexts, (3) investigating the ways in which it had come to be considered “canonical” (or at least worthy of inclusion in anthologies and therefore worth teaching to students), and (4) interrogating its contemporary status in the present (the early 1990s). Hence, for example, we might read Adventures of Huckleberry Finn for its supposedly intrinsic literary value, focusing on Twain’s use of dialect in Huck’s narrative voice or the vivid naturalistic imagery or its allusions to Don Quixote, and so forth. We would also look at the social context at the time of its publication in 1884–85, a moment of national consolidation following the Civil War, for instance, which was also a rather distinct political moment from the mid–1840s setting of the novel. Then we could see how Twain’s comical romance about an eccentric, rustic, Irish adolescent’s adventures along the fringes of society would be reread in the mid-twentieth century as somehow a symbolic narrative of the representative and quintessentially “American” individual, as the novel became canonized as not only a great work of literature but as a crucial part of America’s national narrative. And finally, we could see how Huck Finn was still being used in the 1980s and 1990s to serve an ideological purpose, especially with respect to promoting a liberal agenda vis-à-vis race and racism. (Notably, both the ostensibly traditional Norton and the self-consciously revisionist Heath anthologies included the full text of Twain’s masterpiece; in the latter’s case, this was the only novel to get the full-text representation, such that even the canon reformers felt the impulse to view Huckleberry Finn as “hypercanonical,” to use the term Jonathan coined for this phenomenon.) This multilayered and multifaceted approach to the text and its various contexts typifies Jonathan’s own approach—as is brilliantly on display in his book, Huckleberry Finn as Idol and Target: The Functions of Criticism in Our Time (U of Wisconsin P, 1997)—, and it enriches and enlarges the practice of criticism even as it makes us appreciate the particular literary texts under consideration all the more.

Oh, and another thing about that course: Jonathan managed to get every single student in the class copies of those expensive anthologies—four fat volumes of nearly 2,000 pages apiece—for free. He convinced the people at Norton and Heath that this course was designed for teachers of American literature and, thus, that ours should be treated as desk copies. I don’t recall what the anthologies were going for back then, but in today’s dollars this would be around $350 to $400 that Jonathan saved each of us. Once we got deeper into the semester, I realized that this was not just a cost-saving scheme, but a basic truth: We were getting top-notch training as teachers of U.S. literature. I don’t know if the agents of the booksellers would agree, but everyone in this course became better teachers of the subject thanks to this work. For myself, I can say that, in my years of teaching American literature at the college level, every course I teach in this field partakes of knowledge and practices I learned in Jonathan’s class.

I could say the same for other courses—Jonathan’s Theory of the Novel course sticks with me always, for instance—but that’s just to repeat that Jonathan is fundamentally a teacher. Much as I gained from him in the classroom, I probably learned even more in our conversations outside of class. As all of his former students will be able to confirm, Jonathan has a way of taking the most naïvely ignorant questions or the stupidest comments and revealing their hidden (and certainly unknown to the interlocutor) insights, quickly transposing their simplicity onto another plane, one of enthralling complexity and nuance. I’m sure Jonathan would object to my using terms like "ignorant" or "stupid." As often as I felt ignorant or stupid around him, Jonathan always made me feel that I was more knowledgeable and clever than I realized, but he did so in a way that also challenged me to work harder, to think more clearly, to read more closely, and to write better.

In an article written in honor of the centennial of Northrop Frye’s birth, Jonathan focused on what he called “the scandal of undiscriminating catholicity” in Frye’s criticism. That is, Frye adamantly refused to distinguish “good” from “bad” literature, recognizing the degree to which such evaluations were inevitably tied to contingent factors associated with social class or mere readerly tastes and holding that they had nothing to do with the literary texts in question. I won’t say that Jonathan’s approach to literary and cultural studies is “undiscriminating,” exactly, but he also refuses to dismiss texts or ideas based upon any set belief in what is or is not appropriate to study. This is part of the joy of working with him, as not only is he open to a vast range of potential topics but he also knows so very much about so many things, which means he offers insightful counsel for just about any research project you could undertake.

Of course, Jonathan’s erudition is legendary. I hope I’m remembering this anecdote correctly, but Paul Bové once told me that, back in the late 1970s or early 1980s, a fun activity among members of the boundary 2 group and other colleagues was to try to name a book that Jonathan had not read. Obviously, there were limits to this game, and it likely involved mostly then-canonical works of British and American literature; but it certainly included a lot of obscure and noncanonical works as well, and it also would have covered works of French or German literature, not to mention a good deal of history, philosophy, political theory, and social thought. In any case, more often than not, they would find that not only had Jonathan read the work in question, but he was also readily able to provide some insightful commentary or topical allusions regarding it. (Reportedly, Edward Said would resort to stumping him by naming Arabic texts, but if there were English or French translations available, Jonathan would find them.) Jonathan’s interests are wide-ranging and his knowledge capacious and inclusive, which only enhances his already extraordinary pedagogy.

To put a spin on the famous line from Terence (humani nil a me alienum), one could say that nothing of the humanities is alien to Jonathan Arac. Talk about a role model! I am forever grateful to have been one of his students.

—Robert T. Tally Jr.

Robert T. Tally Jr. (PhD in Critical and Cultural Studies, 1999) is the NEH Distinguished Teaching Professor in the Humanities and Professor of English at Texas State University. His books include Topophrenia: Place, Narrative, and the Spatial Imagination (Indiana UP, 2019), Poe and the Subversion of American Literature: Satire, Fantasy Critique (Bloomsbury, 2014), Fredric Jameson: The Project of Dialectical Criticism (Pluto, 2014), and Spatiality (Routledge, 2013). Tally is also the editor of “Geocriticism and Spatial Literary Studies,” a Palgrave Macmillan book series.