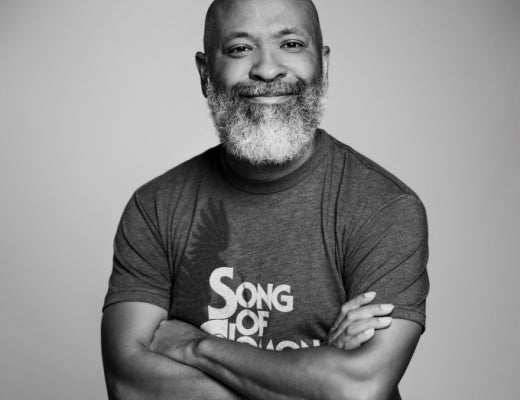

Gary Jackson, a poet, professor, and comic book enthusiast, joined the University of Pittsburgh English faculty in 2023. As a Toi Derricotte Endowed Chair, an assistant professor in the Writing program, and director of the Center for African American Poetry and Poetics (CAAPP), Jackson brings a speculative spirit and deep commitment to Black poetics into the classroom and the community. In an interview with T5F, Jackson shared his lifelong journey from Topeka, Kansas, to Pitt, his Afrofuturist vision, and how poetry—and comics—can make the world more inclusive, imaginative, and alive. Jackson brings a distinctly hybrid sensibility to Pitt, grounded in identity, speculative imagination, and the power of language to hold multitudes.

Since joining Pitt English, Jackson has taught both Readings in Contemporary Poetry and the MFA Poetry Workshop, helping to shape the next generation of writers. Before Pitt, Jackson taught creative writing for over a decade at the College of Charleston in South Carolina.

Jackson’s love for teaching stems from his own education, with a BA in English from Washburn University and an MFA in Poetry from the University of New Mexico.

Born and raised in Topeka, Kansas, Jackson’s path into poetry was shaped less by a plan and more by instinct. As an undergraduate in Kansas, he was originally planning to study fiction writing. Yet, to make ends meet, Jackson had to work a full-time job, which ended up being the “graveyard” shift at a yearbook printing plant. “I’d get off at 7 a.m., nap, go to class, nap, then work again,” Jackson recalled.

During his late-night shifts, Jackson would feel inspired to jot down quick stories. Though he had little time to write lengthy fiction, shorter-form writing became his outlet. As Jackson noted, “My stories just got shorter and shorter until they were kind of poems.”

An undergraduate poetry class and an encouraging professor sealed the shift for Jackson.

“She thought I had something,” he said. “I realized poetry is such an open container. . . . There’s elements of narrative, lyricism, formalism with traditional poetic forms, but also more experimental or avant-garde work in forms, too.”

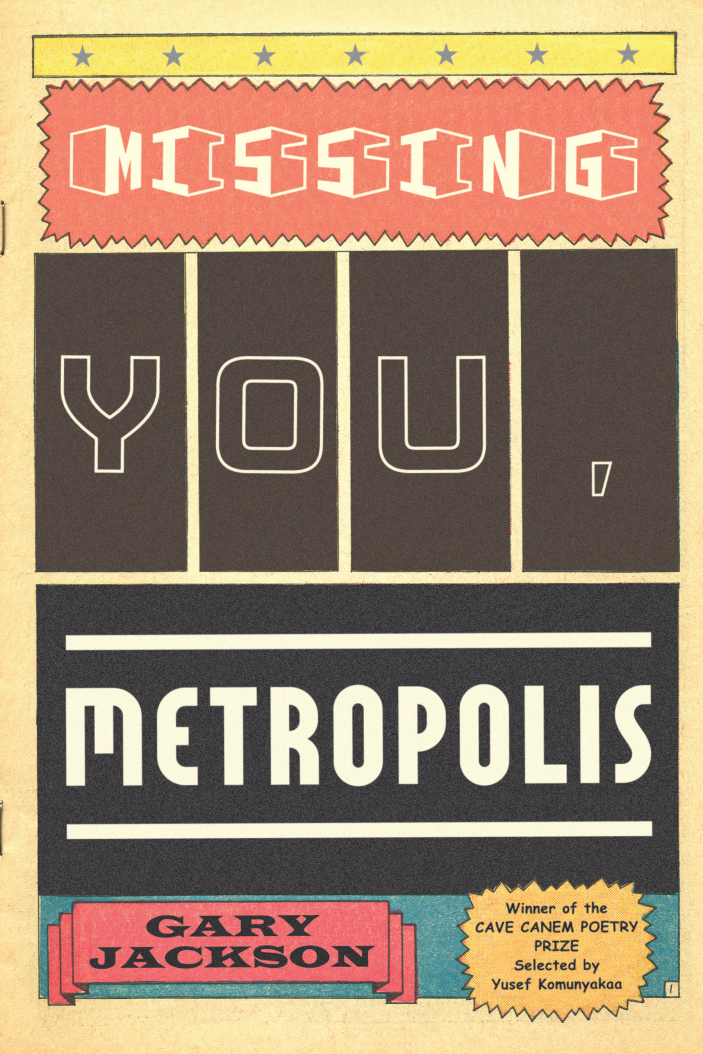

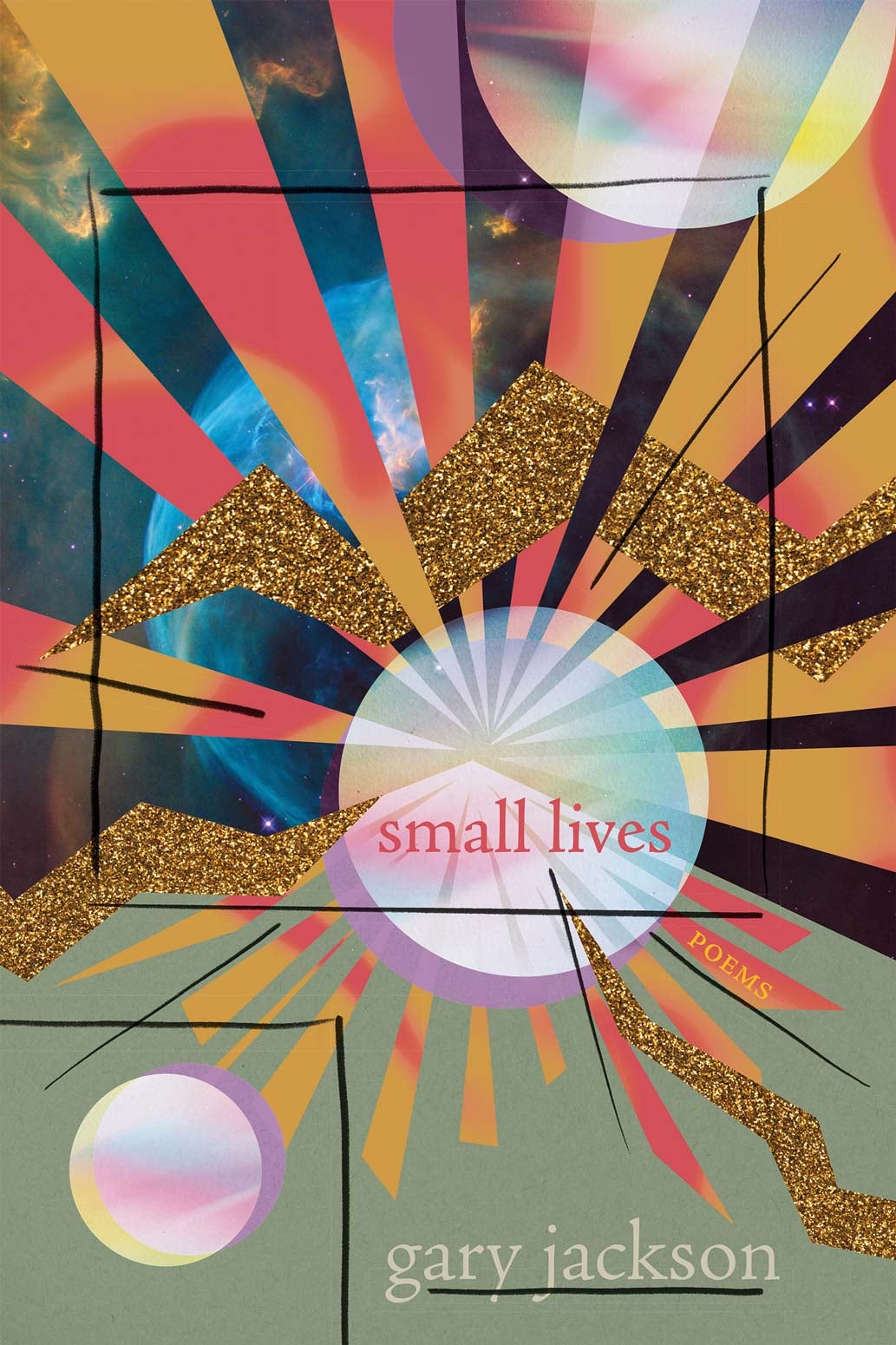

That “open container” philosophy defines much of Jackson’s writing, from Missing You, Metropolis (Graywolf Press, 2010)—full of superhero-inflected coming-of-age poems—to his forthcoming project, small lives (University of New Mexico Press, 2025), a speculative poetry collection that will be arriving this fall. Jackson describes it as “a novel in verse.” The book centers on three superheroes navigating an alternate America where superpowers double as metaphors for Blackness and otherness.

Much of Jackson’s work is infused with Afrofuturism—though he claims he’s not an expert. The term, Jackson said, is “at its core, a confluence of Blackness, technological advancement, and speculative work that actualizes the full breadth of life from the African Diaspora. Afrofuturism involves Black authors writing themselves into their own future, present, and past. This is expressed not just in literature, but also in music, visual art, fashion, and other artistic modalities."

Jackson’s childhood obsession with comic books plays a big part in his involvement with Afrofuturism and speculative poetry. Comics were such a formative part of how Jackson grew up that they became the mode in which he learned to process his own life. “Those were the myths I grew up learning, more so than religion,” he said. “Comic books were kind of my religion."

His favorite superhero? He laughed and said, “It’s Spider-Man.” For Jackson, Peter Parker’s struggles—paying rent, flunking college, feeling unseen—were more relatable than life in the palatial settings of most other heroes. “He mirrored my own experience in a way others didn’t.”

Through superheroes, Jackson can imagine himself, and other Black people, “in any realm that’s possible.” “If you can imagine it, you can see it,” he observed. “And if you can see it, you can realize it eventually.”

This speculative approach extends beyond his books: Jackson has been collaborating with a visual artist to produce a hybrid project blending poetry and comic book panels. The results, which are still in development, may not fit neatly into any single genre—but that’s the point. “It’s just fun to write and collaborate,” he said.

His work as a poet has appeared in numerous literary journals, including Callaloo, The Los Angeles Review of Books,The Sun, and Copper Nickel, as well as various anthologies. His first poetry collection, Missing You, Metropolis, won the 2009 Cave Cave Canem Poetry Prize. Another of his poetry collections, origin story (University of New Mexico Press, 2021), was a part of the Mary Burritt Christiansen Poetry Series—which Jackson’s upcoming book, small lives, will also be a part of.

With Cynthia Manick and Len Lawson, Jackson coedited The Future of Black: Afrofuturism, Black Comics, and Superhero Poetry (Blair, 2021), a hybrid anthology exploring superhero narratives as a form of inclusive speculative Black poetics.

After 12 years of teaching at the College of Charleston, Jackson found himself craving change. “I was a little tired of living in a city that was highly tourist centered,” he said, “as fun as it was to live in the South.” He and his wife were ready to relocate, and Pitt offered more than a new job.

“What I was attracted to was the level of resources and support Pitt provides its faculty,” he said. “I’ve heard great things about the students there. The poetry program is highly valued, especially in its dedication to Black poetry.”

That reputation—bolstered by CAAPP’s national impact through events, a growing archive, and more—was already familiar to Jackson. Back in 2011, during his time as a Cave Canem fellow, he visited Pittsburgh for a reading at City of Asylum. Sharing a lineup with the likes of Terrance Hayes, Toi Derricotte, and Cornelius Eady left a lasting impression.

“It has a very storied and rich legacy, especially in regard to Black poetry,” Jackson said.

Now, he’s part of that legacy, through both teaching and steering CAAPP into its next chapter.

Now, he’s part of that legacy, through both teaching and steering CAAPP into its next chapter.

Teaching across education levels has shaped his own evolution as a poet and mentor. With undergraduates, Jackson emphasizes discovery. “They’re so young in their writing practice that they’re very eager,” he said. “There’s such an openness to unlearn the ways we’re taught to be afraid of poetry.” He encourages students to shed formulaic poetry approaches and write poems that sound like themselves—not what they think poetry is “supposed” to be.

“It’s so gratifying to watch students see the light bulbs go off,” Jackson said.

With graduate students, the work takes a different shape. “They usually have an idea of what they want to write about or what they’re trying to process,” Jackson explained. “So it’s not a one-size-fits-all approach—it’s more like: What are you trying to do? Let’s build a knowledge base that can inform your practice.”

The goal, he says, is always the same: “to meet students where they are” and empower them to move forward.

As director of CAAPP, Jackson is committed to fostering that sense of joyful discovery across Pittsburgh and beyond. The center, he said, interprets “poetics” broadly—embracing all artistic practices as valid forms of expression. CAAPP focuses on being a resource that “spotlights and celebrates Black art,” he said, “but we also illuminate process—how artists make work and how they sustain it.”

Recent events have included everything from readings to cross-genre workshops exploring ecological desire. Jackson sees such programming as vital, especially for young Black artists who rarely get to witness how a creative career is built. “We try to archive those processes,” he said. “It’s very educational for any young artist, but especially young Black artists, to see other established Black artists enter the sphere of artistic work.”

That ethos of access shapes his community outreach goals, too. Jackson’s vision includes programming not just for Pitt students, but for Pittsburghers who might not have access to classrooms, which is why he’s been in conversation with the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh to brainstorm about community engagement.

“You don’t need many resources to write a poem,” he said. “If you have a pencil and paper and imagination, you can write a poem. And a poem can help you process your own experience.”

In a political climate where the arts and humanities are increasingly under attack, poetry is more necessary than ever. “A poem can convey your experience to someone who isn’t you. And right now, so much of what we’re witnessing is this inability or unwillingness to share our experiences with each other, to listen.” Poetry, Jackson believes, offers a quiet form of resistance, rooted in empathy.

For students hesitant to pursue poetry—whether out of fear or practicality—Jackson offers a dual response. First, he reminds them that they don’t need permission. In fact, he encourages his students to have a “wildness” when they write poetry. “You can write whatever you want,” he reminds students. Second, he dispels the myth that poetry must be a profession. “Some of the best poets I’ve taught were in STEM,” Jackson recalled. (The most recent winner of the Cave Canem Prize, Brandon Kilbourne, is an evolutionary biologist whose first full-length book of poems, Natural History, will be published by Graywolf this fall.)

“Poetry can just be this thing you do,” Jackson said. “I think as long as you’re able to make some time for it, poetry is always there.”

When Jackson isn’t writing, teaching, or running CAAPP, he’s exploring Pittsburgh’s food scene. “I have a list of restaurants I need to try,” he said. He loves cooking, too, and calls it his “love language.” Between meals and watching “bad TV,” he’s slowly getting to know the city he now calls home.

But even in rest, the work persists. “Writing is how I exist in the world,” he said. “It’s how I interact with everything around me.”

And in that, Gary Jackson practices what he teaches—using poetry not just as a career, but as a way of being fully, imaginatively alive.

—Briana Bindus

Briana Bindus, associate editor for The Fifth Floor, is a rising senior pursuing a Bachelor of Philosophy degree in English Literature and Communication. She believes in empowering all voices, which she aims to do through her passion for journalism.