Chuck Kinder in Key Largo

On Friday, May 3, former Professor and Director of Writing Chuck Kinder passed away in Florida. Upon learning of his death, outgoing Chair Don Bialostosky wrote to faculty, "I'm grateful to have gotten to know Chuck at the end of his career and in his retirement. His warmth, wit, and joie de vivre enlivened all who knew him." Kinder retired in 2014. He and his wife, Diane Cecily, have been living in Key Largo in recent years; Distinguished Professor Colin MacCabe visited them there and completed an interview for The Fifth Floor in 2012. Having been a close friend of the late fiction writer Raymond Carver and the inspiration for the Grady Tripp character in alumnus Michael Chabon's novel The Wonder Boys, Kinder's passing has been marked by obits in both local and national newspapers, from the New York Times to the Washington Post. Closer to Pitt's English department, Kinder was famous only for who he was—a storyteller, teacher, colleague, and friend. His and his wife's generous hospitality is especially remembered by many an MFA grad.

Chuck Kinder's books include Last Mountain Dancer: Hard-Earned Lessons in Love, Loss, and Honky-Tonk Outlaw Life (creative nonfiction, Carroll & Graf, 2004), Honeymooners: A Cautionary Tale (novel, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2001), The Silver Ghost (novel, Harcourt Brace, 1979), and Snakehunter (novel, Alfred A. Knopf, 1973). In what he liked to call his "dotage," he published a collection of poems, Hot Jewels, with the Pittsburgh-based Six Gallery Press in 2018.

Below are a few reflections on Chuck Kinder's life as a friend to his students and fellow writers over the years. The first is by Pulitzer prize-winning novelist Richard Ford, who sent the following short piece to be read at a 2014 English department event celebrating Kinder's retirement. Next are reflections by MFA alumni and Pitt English faculty Jeff Oaks and Keely Bowers.

Photo courtesy of Diane Cecily

____________________________________________________________________________________

For Chuck

By Richard Ford

“A friend is the hope of the heart,” Emerson wrote. Which is all well ‘n good; but here’s something closer to the truth. ...

In 1979, I was living in New Jersey, failing badly at writing a novel. Ray Carver said, “You need to go out to San Francisco and see my friend Chuck.” Why these two sentences would follow one another I don’t know. At the time, they made sense. In California, in 1979, it was still the 60s. Connections were fairly Orphic.

But I got on a bus at the Port Authority—the bus was all I had money for—and rode the 12,000 miles out to San Francisco to see Ray’s great friend Chuck. On the way, either to keep myself awake or to put myself to sleep, I read Snakehunter, which I liked very much. But from that, and from things Carver had told me, I sort of knew what I was getting myself into: guys who drank and smoked a lot of dope, guys who liked to fight (or at least liked their friends to fight and then to be able to talk about it as if they’d done the fighting); guys who wore cowboy boots but weren’t really cowboys, guys who had glamorous wives who didn’t take any shit; guys who’d read everything, had been to Stanford, had southern someplace back in their lineage, but also Montana, and maybe Texas, and whose names began either with C or K: Crawford, Crumley, Kittredge, Carver ... Kinder. In other words, it was the highly attractive, rough-hewn, Jack London version of American literary ethos—a kind of boozy, semiviolent demimond ... with books. Altogether—at least in Carver’s estimate—it was an ethos I needed and that was going to cure me of novel failure, if I could only draw close enough to it.

Snakehunter, by Chuck Kinder

I’d been to San Francisco maybe once. I was 35, but didn’t like California—north or south. I had a feeling that anybody who lived there by choice was probably ducking something difficult and important, and was on the run from the real America, which was back east of the mountains, maybe even east of the Mississippi—where I lived. Kinder, I thought, was probably that way. I mean if you were born in West Virginia and were a novelist, why would you ever leave—unless you were a complete pussy?

Ray had told me Chuck lived on California Street. Which seemed to mean something. Something mystical was involved in that address—in the spirit of ... “Well, of course he lives on California Street.” That was meaningful, possibly necessary. I was getting a picture in my mind of these tough guys wearing cowboy boots and fighting and writing books, but who were also effete and sensitive and attended poetry readings and maybe wrote poems themselves, and volunteered in daycares and food banks.

It was summer. I found a hotel on Union Square. The Manx Hotel, named after a tailless cat. They put up a cyclone fence up out front every night, so you couldn’t go in or out after ten.

I got a map. I found California Street. It was very long. Maybe I could ride the cable car to where this Chuck lived, but the street car didn’t seem to go that far. So I walked. I don’t remember Chuck’s house number on California Street, but it was a very big number, which meant it was a long walk, made longer by my not knowing where I was, or why. What was this guy going to do for me? He was Carver’s friend. I guess that was it.

I got to the house mid-afternoon. Two-thirty or so. I rang the doorbell, and a very pretty woman with a beautiful smile, whom I later came to know was Diane, said hello, yes, Chuck Kinder lived there. But he was with his friend Max, and they’d gone around the block to a bar. As I said, it was 2:30. Not 5 or 6 o’clock. They were at the bar already. And who was this Max? The woman didn’t know me, seemed slightly suspicious, but said I could go around there. I’d recognize them. She didn’t say precisely how. It was a matter of faith. No one else would look like them.

So, I walked down the block and turned on a side street. I wasn’t particularly used to just presenting myself to other writers. It seemed presumptuous. What did I want, after all? Money? To be a member of the "K & C" club? Ford. "F. I didn’t fit. I was a southerner, okay. But I lived in New Jersey. I taught at Princeton. I owned a house. I didn’t wear cowboy boots. I had written one book, but it hadn’t done very well. Stanford had turned me down. I was Carver’s friend. But that might mean I needed to be beaten up. I was the pussy.

Halfway down the street to the bar, two men were walking side-by-side in my direction. These were big men. They were wearing boots, had messy beards and scruffy hair. They were talking loud and laughing, but somehow also scowling, as if maybe they switched from one mood to the other fairly easily and often. These two kinda looked like bikers, but they also kinda looked like unstable, marginal people who in a month could be panhandling on the street and screaming at passersby. They were also not at all sober. That was clear. Which meant they were probably volatile and might not distinguish hostility from friendship and maybe didn’t even care. Jesus, I thought. What kind of neighborhood was this? One that was full of people to avoid. Which I did. They kept walking straight toward me, side-by-side, a two-person phalanx. I stepped right down off the curb to get out of their way. Though they eyed me in an unfriendly way—as much for getting off the sidewalk as they would’ve if I’d stayed on it. There was no winning. There was just staying clear.

I got past these men and went another block. Here was the bar. A working man’s dive. I went in. But it was empty. “What can I do you for?” the bartender said. “Looking for Chuck Kinder,” I said. “You must’ve passed him on the street,” the bartender said. “He and Max Crawford just left. Pretty good head of steam on both of them. You can probably catch him on the way back up to California Street. That’s where he lives.”

A friend is the hope of the heart, I suppose. As unlikely as that “meeting” was that summer day, it was also the beginning of a 35-year love affair—one I have with Chuck—who is a pussy. And I am not. In its way, this friendship’s beginning was highly literary, since writing teaches us that we never know the outcome of most things, and if we just go on appearances and convention and what’s expected, we’ll often be very wrong. The best outcomes have to be imagined. Where there wasn’t anything to begin with, we have to make something new be. It’s a writer’s version of hoping. Chuck and I’ve been replenishing this life-friendship back and forth for all these years. Life wouldn’t be life without him. I really can’t believe it’s been that long, and that he’s as old as he is and already headed to Florida, when I’m just getting into my prime. My only other hope is that he comes to his senses, like he did in California, and comes back where he belongs—where it’s cold in the winter like it oughta be, and there are good bars, and you know east from west, and the tide’s always in, and everybody loves you. Like we all do.

Jeff Oaks, MFA Alumnus, Assistant Director of the Writing Program

"Chuck Kinder has died. Not only was he the former director of the Writing Program, friend to and teacher of so many famous writers, but he was one of the kindest people I’ve known. Not only did he and Diane throw, in the old days when you could do things like this, the wildest and most hilariously extravagant parties at their Squirrel Hill house, parties where everyone used to talk, drink, eat, celebrate, and get to know each other outside the (clap)trappings of our professional lives; but he once told me his whole “pedagogy” (a word he distrusted) could be summed up in asking a single question— “What if...?” —over and over again until a piece is done. Although he’ll be remembered in the larger world as the model for Grady Tripp in Wonder Boys, he’ll also be remembered here as a wily, generous, quietly subversive teacher to judge from all my friends who took his classes. For him, a Workshop was a serious place where writers talked to other writers and tried to help them make stories better, smarter, more beautiful and deeper. You didn’t waste your time or anyone else’s with anything other than your best self. His own work was always wildly funny at the same time it glowed with great human ache. He and Diane sheltered an awful lot of people in that enormous house. Some part of me will always be leaning on a wall there, young, poor, nervous, but thrilled to be among other writers telling each other stories, rooms erupting with laughter, feeling completely full. He invited a lot of people into a fuller life who did not have much more than some talent with words and hope. He will be missed by many, many of us who still, like he did, believe in the enormous value of a person telling faithfully the stories of his or her or their survival, reclamation, and failure. That work is hard enough to do."

__________________________________________________________________________________________

Keely Bowers, MFA Alumna, Instructor

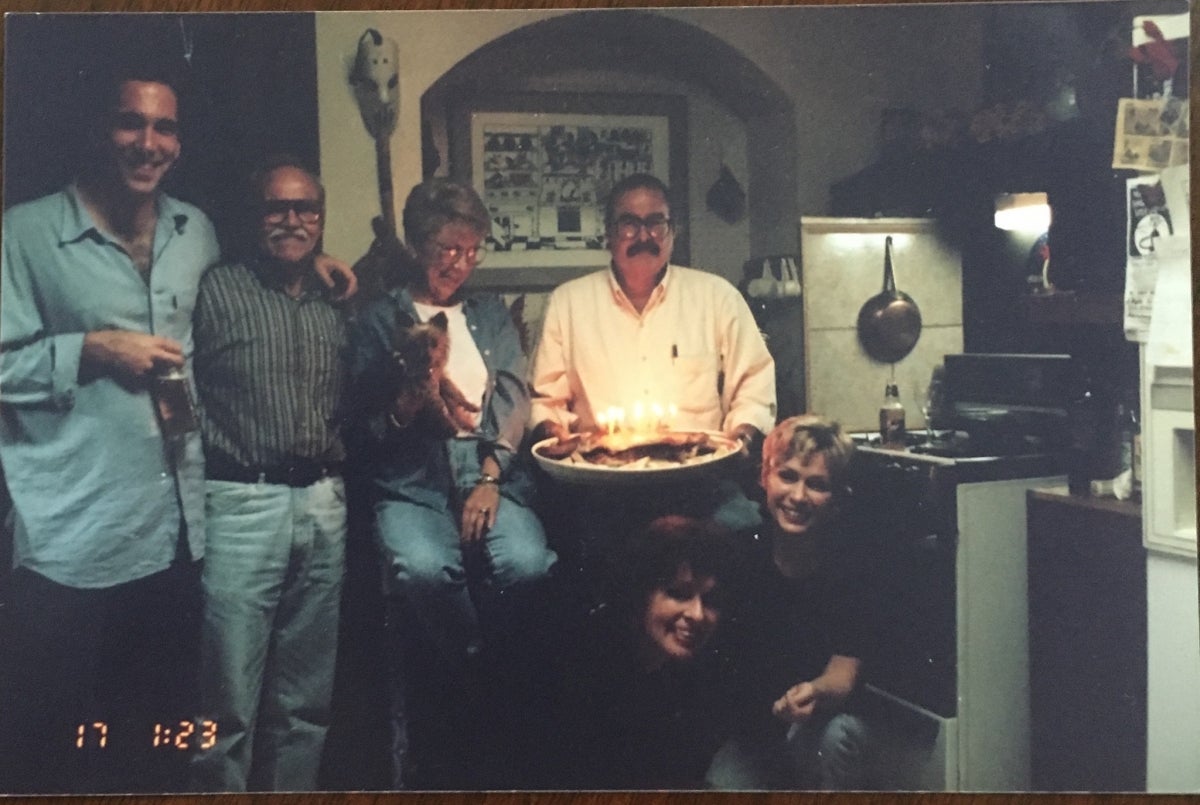

MFA Alumnus Roger LePage and Family, with Chuck and Diane (2000?)

"The past blew in yesterday and took a seat at my table, set me looking through all these boxes of old photographs. I’m sitting now by the screen door in the soft gust of lilacs and Sunday rain, wading through memories. I have so many so close to my heart, far too many to detail. And many of you have written an abundant and beautiful share of your own. Chuck Kinder gave so much to all of us and had a remarkable way of making us believe things are possible —magic even—on those torchlit backyard pond-life nights with the little fire burning, the sleeping fish, starlight, and all the shadow ghosts of stories. For a giant, joyful, unmatchable, precious part of my life, Chuck and Diane gave me heart and big, big laughter, music, a garden, firelight, family, stories, Sunday suppers, home."

Photo courtesy of Keely Bowers

You can make a donation in his memory by giving to the Nordan/Kinder Fund for Fiction, which supports our graduate and undergraduate writers in telling good stories and pursuing the writing life.